Project Details

Tariffs and reciprocal tariffs: who plays which game?

Dr. Simon Jantschgi & Prof. Dr. Heinrich Nax

University of Zurich

Juni Issue of Die Volkswirtschaft

See Zölle und Gegenzölle: Wer spielt welches Spiel? – Die Volkswirtschaft for the German original article, and Mesures douanières et contre-mesures: qui joue à quoi? – La Vie économique for French.

Lead. Game theory views tariffs not just as taxes but as moves in a strategic game played on top of the international trade network. A sudden tariff, no retaliation or costly escalation, may all seem irrational moves, but might also all work out, as their value depends not only on the move itself but on how the rest of the world responds.

The idea of a tariff is tempting. Can a country by imposing tariffs and import duties on its competitors boost domestic industries and skim profits off its trade partners?

The answer to this question is not simple. Almost surely, as a direct consequence of tariffs, price levels domestically will rise.[1] Moreover, trade partners may retaliate, triggering a spiral of reciprocal tariffs that may hurt domestic industry too. Indeed, history issues warning examples like the 1960s “Chicken Wars” that began with European import duties on US chicken, reciprocated with the “Chicken Tax” on lightweight trucks from outside the US, triggering a chain of tariff escalations, the consequences of which in terms of industrial specialization can be felt on both sides of the Atlantic until today.[2] In other cases, many import restrictions and tariffs on, including Swiss examples such as cheese, meat or seasonal fruit, may protect local produce and not lead to escalation.

Tariffs are clearly more than tax levers — they are strategic moves in an interdependent tariff game played on top of international trade. To understand the costs and benefits associated with the tariff game — and why the game of tariffs may end up with cooperation, retaliation, and standstill — we need game theory: the mathematical language of strategic decision-making.[3] Game theory doesn’t just model what’s best for one player, but how each decision shapes and reshapes the choices of others. Game theory helps understand players’ incentives, possible responses, and the patterns that emerge when players anticipate each other’s moves.

In a game, each player chooses an action from a set of options available to them, here governments setting tariffs. Once all players have made their choices, the result is an outcome, with a specific payoff for each player — a measure of success or failure. A player’s action is a best response if it yields the highest payoff given others’ actions. A Nash Equilibrium occurs when everyone is playing a best response to the actions of the others, so that no one can gain by unilaterally deviating from it.

The simplest version of a tariff game has two players choosing between free trade or tariff. The payoff for each country depends not just on its own choice, but on the combination of both countries’ actions. Depending on how the economies respond to different tariff situations, countries face different strategic incentives, which can give rise to different equilibrium outcomes. Three classical examples of games are relevant:

Scenario 1: The tariff game as a Prisoner’s Dilemma game.

With this view of the game, mutual free trade maximizes overall welfare — both countries are better off together when markets stay open. However, each country has an incentive to unilaterally impose tariffs. If one country plays tariff, the other is worse off and has every reason to retaliate, not for fairness reasons, but based on immediate economic self-interest. As a result, in equilibrium, both sides impose tariffs.

Scenario 2: The tariff game as a Chicken Game.

Again, mutual free trade would be desirable but countries unilaterally win by imposing tariffs on open trade partners. However, in contrast to the Prisoner’s Dilemma game, mutual tariffs result in an outcome that is so bad that given tariffs imposed on oneself the unilateral better response may be not to respond to tariffs with tariffs. Therefore, the equilibrium is asymmetric, with one side imposing tariffs, the other not. Each country prefers the equilibrium where they play tariffs themselves, but prefers not to play tariff if the other country does.

Scenario 3: The tariff game as a Stag Hunt game.

In this scenario, both sides have a choice between opening up to trade at all, or remaining economically isolated. Mutual openness generates the highest gains for both. Mutual isolation is less efficient, but sometimes more stable, as the real danger lies in the asymmetric outcomes: if one country opens while the other stays closed, the open country specializes and but gains no access to the other economy in return, while the closed country operates self-sufficiently. That’s why in this version of the game neither side wants to be open without guarantees of openness in return.

|

Country B: |

Country B: |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Country A: |

(3,3) |

(0,2) |

|

Country A: |

(2,0) |

(2,2) |

|

Country B: |

Country B: |

|

|

Country A: |

(3,3) |

(1,4) |

|

Country A: |

(4,1) |

(0,0) |

|

Country B: |

Country B: |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Country A: |

(3,3) |

(1,4) |

|

Country A: |

(4,1) |

(2,2) |

So what kind of game are we playing when it comes to tariffs?

The truth is: it’s not immediately clear. No bilateral trade relation is ever as simple or exactly like any of the three simplified two-by-two games above, yet at any moment different bilateral trade relations in the global trade network may in essence share incentive structures with one of them.

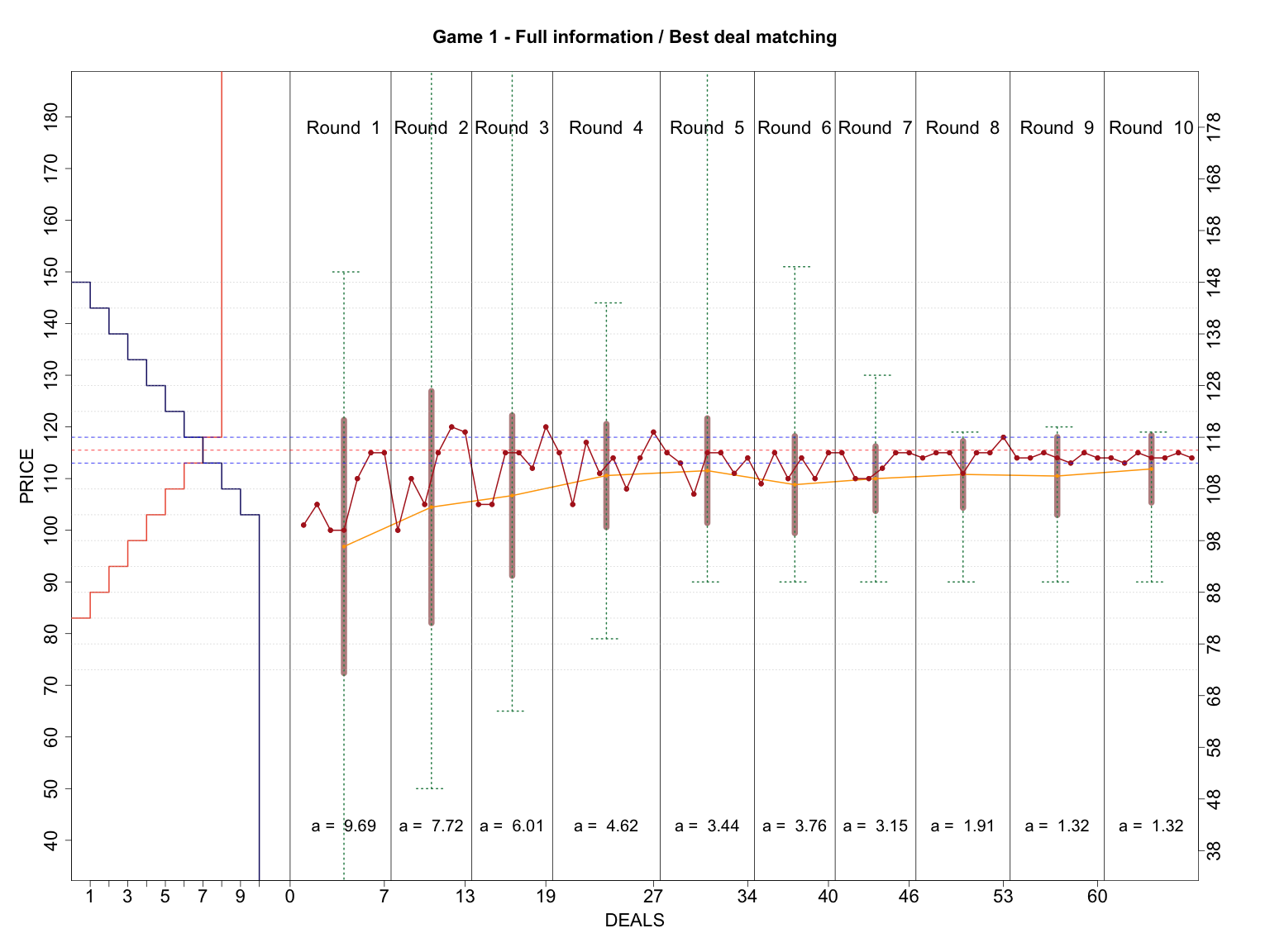

Most importantly, whatever the momentary game may be, trade relationships unfold over time, which is why countries take decisions with one eye toward the past and the other toward future consequences. What matters is not only what game is being played right now — but how the games are played over time. With repetition, countries can condition their strategies on past behavior of others, and can build reputations for toughness, or signal willingness to yield in future rounds. An example of a well-known repeated game strategy is “tit for tat:” maybe start by cooperating, but then do whatever the other side did last time. Repeated game strategies can help sustain cooperation as the threat of future retaliation makes defection less attractive today.

By itself, the fact that a game is repeated does not guarantee cooperation. Harmful moves, even harmful for oneself, may be used as signals of aggression to shift expectations. This means that countries may impose or rather threaten to impose tariffs, not to win that round, but to appear tough and to build a reputation for future negotiations in the hope of shifting to a more desirable equilibrium.[4] The threat of tariffs therefore may only be temporary and perhaps ought not be reciprocated by the other countries, as the game will likely resettle in the previous equilibrium once the threat of tariffs is again removed for its inconsequentiality.

Tariffs may also be imposed seriously, not just as threats, in particular if a country considers itself to be stuck in a bad equilibrium. Such a country might introduce drastic tariffs to disrupt the current equilibrium, accepting short- or even mid-term losses and escalation of tariffication, in the hope of ending up in a better equilibrium in the long-run. Whether escalation actually occurs will depend on the counterparties’ assessment of its relative positional strengths. We can think of such considerations somewhat along the lines of escalation-dominance as discussed at the height of the Cold War, which captures whether countries expect to come out on top or not in case of escalation.[5] Indeed, if both parties believe to be escalation-dominant, maybe for different reasons or based on different metrics, long and painful escalation dynamics may indeed result.

What, then, is a rational strategy in the tariff game?

As we aimed to illustrate with our examples of games, what is a rational strategy depends on the bigger picture.[6] A relatively minor tariff that seemed beneficial in isolation may unravel if other countries respond harshly in return. While a major tariff that appeared reckless and even self-defeating in the short run may turn out to be a successful strategic play if it succeeds to shift expectations, build reputation, or escape an unfavourable equilibrium.

Game theory cautions us not to mistake asymmetry, aggression, or retaliation for irrationality — even if these moves may seem puzzling, excessive, or unfair at first glance. In repeated interactions, threats, bluffs, restraint, or even costly escalations may all serve a purpose. Whether these moves succeed depends not just on the strategy itself, but on how the rest of the world reacts.

[1] For an economic analysis, see Foellmi>>> in this issue.

[2] For an early game-theoretic analysis of the Chicken Wars, see Jonathan R Macey, "Chicken Wars as Prisoners' Dilemma: What's in a Game." Notre Dame L. Rev. 447. 1989.

[3] Game Theory textbook; see Martin J Osborne and Ariel Rubinstein, A course in Game Theory. MIT Press. 1994.

[4] The logic of the Chain Store Paradox; see Reinhard Selten, "The chain store paradox." Theory and Decision 9(2): 127-159. 1978.

[5] Escalation Dominance; as discussed in Paul K Davis and Peter J. E Stan, “Concepts and Models of Escalation.” Rand Strategy Assessment Center Report. 1984.

[6] For a scenario analysis of the US tariff situation, see Gersbach>>> in this issue.

- Documents Download the documents related to this project here

- Category General info

- Link to experiment demo https://dievolkswirtschaft.ch/de/2025/06/zoelle-und-gegenzoelle-wer-spielt-welches-spiel/

- Link to user demo https://dievolkswirtschaft.ch/de/2025/06/zoelle-und-gegenzoelle-wer-spielt-welches-spiel/